University of Frankfurt

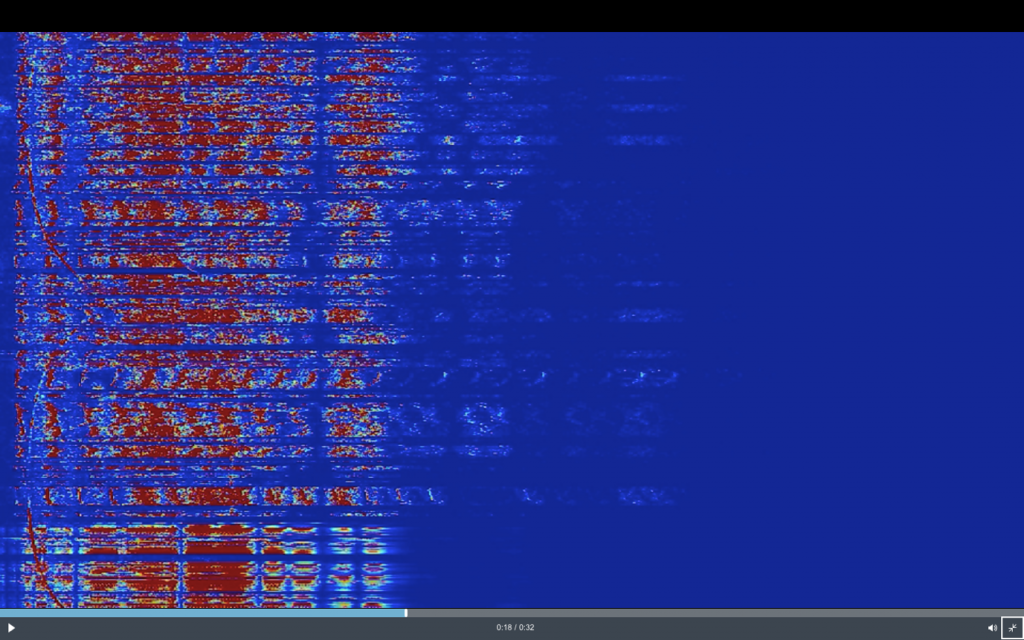

(Fig 1: screen capture from a video made by the Israeli Defense Force’s Technological Lab for Tracking and Exposing Tunnels)

Author’s note: The essay was originally given as a talk in a lecture series on machine vision, titled “L’image à l’épreuve des machines,” hosted by the Parisian gallery Le Bal, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales and the Sorbonne. The lecture was written in October 2021, and except two very short moments in the text, it does not account for the events that followed October 7th 2023: Hamas attack and the Israeli counter attack that is still ongoing while I write this note in December 2024. I chose not to revise the essay according to the prism of the contemporary genocidal moment, as I believe it captures the continuous history of sovereign violence in Gaza. The past undercurrents described below can perhaps contextualize the rapturous and destructive present.

I.

“It Looks Like a Snake and Moves Like a Snake”

In June 2009, on the Israeli Channel 2 evening news, Israel Institute of Technology, The Technion, and the Israeli Ministry of Defense launched a new technological development meant, as the news item announced, to serve the military in its subterranean warfare. “It looks like a snake and moves like a snake! But it’s actually a camera” announced the news anchor, presenting a reptilian robot, made of mechanic vertebrates. The lethal reptile is designed to mimic modular locomotion and weaponized with infrared camera, high-speed and high-resolution cameras, movement sensors, and explosives. Celebrated as the avant-garde of military tech, The Snake was designated to operate in spheres beyond the combatants reach, as the reporters affirms: “In Gaza’s tunnels, Hezbollah’s bunkers, cracks in the ground or narrow passages through buildings’ ruins.” The news item describes the robot as a decisive component of the “future battlefield” and in rescue missions, commissioned to collect intelligence, live stream data and eliminate suspected entities in the depth of the ground or the aftermath of urban disaster.

In the time of its launching, The Snake was a new technological deus ex-machina for what was known in Israel as “the tunnels terror,” a web of underground passageways under the sieged city of Gaza, perceived as a menacing threat, hosting clandestine movements (and today, where Israeli hostages are imprisoned). Side by side with their strategic use by Hamas, the tunnels are also a crucial civil infrastructure for the besieged city of Gaza, an illicit artery that supplies food, construction materials, ammunition and other goods. How does The Snake operate in the tunnels, beyond clear sight, in a space both vital and lethal? Can its operation in such liminal space rearticulate the sovereign violence inflicted by Israel on Palestinians?

The Snake Robot belongs to a growing field of BRML: Biometric Robotics and Machine Learning. Its developers also draw on optic fibers and their use in penetrative medical technology, for example, endoscopy. Here, it is used to penetrate and travel not inside bodies, but the pharynx of terrestrial terrains. In the news item the undulating robot is constantly compared with its biological counterpart, its capacity to operate in spaces beyond human reach or vision is highlighted, and so does its applicability and usability across different spheres of human activity: medicine, agriculture, military and crisis management, among others.

Side by side with recent advancements in biomechanics The Snake demonstrates the exponentially growing reliance on optics and machine learning in warfare operations. Warfare optics open a visual field defined not by a language of representation, but a logic of operation. Such processes, of mechanization- and computation-by-optics is not exclusive to warfare, but happens across infrastructural and logistical operations. A different form of vision now encompasses executionary force, it acts, and with machine learning: a sight, its epistemic and cognitive processing, and its tentative operation are all condensed to the surface of the image. Thomas Keenan rightfully observes that the extension of human vision to facilitate various logistics, from engineering to surveillance, was a prevalence modus-operandi for good few decades by now. With new technological developments, he contends, processes of interpretation, deliberation and consideration traditionally done by humans are being mechanized exponentially. Harun Farocki’s writing and work on the operative image already proposes images that act, but with Keenan we need to consider the increasing complexity of such actions. Now that images are added with a “thinking” faculty, their mandate to act is ever more forceful. Images are no longer the initiators of human reflection that respectively lead to action, but executive agents themselves.

New vision technologies promote a belief in total vision, determining human and more-than-human entities. Operative images, purposed to enhance human vision, are positioned on the threshold of visibility. Images that operate puts pressure on the very notion of vision and also complicate the distinct frames of the operation itself. Operations, tell us the sociologists and political thinkers Brett Nielson and Sandro Mezzadra, are complex and branched-out. Operations are not just about a procedural set of actions, inputs and outputs or hard facts, but include, at times even determined by, their potentialities and imaginaries, their phantasmatic envisioning and their echoing aftermaths. The crossing of functions and usability that The Snake Robot demonstrates, where the technology is utilized either for rescue or elimination, in cultivating food or the aftermath of urban disaster, already displaces the concreteness of actions. It points at larger questions about the technological regime that organizes modern life. With this new, total logic visual operations reorganize and cohere bodies, objects and terrains from the inside out.

(Fig 1: screen capture from video demonstration of the Snake Robot, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-dzZBa6TQE)

Within the discipline of media studies writings on violence and the visual have distinctively prioritized verticality as a visual paradigm through which to think of warfare, and the control over space. French philosopher Paul Virilio–perhaps one of the dominant figures in theorizing the relationship between vision and war—made this ominous connection by focusing on the look from above. The work of media scholar, Lisa Parks, critical geographer Steven Graham and the architect Eyal Weizmann has similarly reinforced the hegemony of verticality. In her cultural history of aerial vision, Caren Kaplan provides a more layered reading of the connections between visual technology and military, adding to it notions of fascination and control. There is a connection reinforced again and again between the totality of vision, vertical distance and control. In contemporary battle field media is used often for the purpose of operating from a distance or distance operation: surveillance, targeted killing, surgical elimination, all are means of precision, but also designed with the aim of keeping the operator safer. Verticality, distance, altitude are strategic components in these kind of operations.

The surface again and again marks a threshold of visibility. With The Snake we move into subterranean terrains. In the depth, the optical aspect is somehow compromised even blocked, we’re no longer in plain sight. With the compromise of the visual regime, power and its operative performativity becomes speculative, even fictive. Going inside, I will argue, make bodies and landscapes amorphic, even abstract. While distance is still a dominant modus operandi, interiority adds a notion of odd proximity, even intimacy.

II.

Penetrative Aesthetic

During the Israeli attacks on Gaza in May 2021, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) performed a sophisticated maneuver: sending a vague message to international media, moving forces and using heavy artillery at the border of the Gaza strip, it created the impression that it is preparing for a ground invasion. Such impression was meant to trick Hamas to withdraw into the underground Gaza tunnels. While Hamas will be hiding in the tunnels, the IDF will use aerial strikes with a recently developed secret weapon, a bomb that with the help of new technology can penetrate the terrain, and in a surgical precision collapse the tunnel, on top of those hiding in it. Some parts of this maneuver are commonly used war strategies, for example, the use of trickery, the visible movement of forces only to tease a corresponding movement, or the surprise element. A subterranean architecture of networked passages is as ancient as warfare itself and was always there in excess to what happens in plain sight. Tunnels, notes the former colonel, Dr. Shaul Shay, are used in contemporary war mostly in asymmetrical conflicts by the inferior side. Tunnels warfare, Shay concludes, necessitates a combined geological and strategic approach. The failed trickery shows us the performative and speculative component of warfare, but mostly, what it brings to the surface is the way the military works with interiority, and how it weaponizes its enemy’s infrastructure in a traverse maneuver: rather than find a bait to lead the warriors outside, where they are dangerously exposed and visible—the conventional maneuver—to make them go inside, and then to bury them under their own design.

In an article from 2006 the architect and head of the research agency Forensic Architecture, Eyal Weizman describes how in the early 2000 the IDF adopted a military tactics that they termed “traverse geometry.” Operating in Palestinian refugee camps in Nablus and Jenin, the troops avoided the streets, alleys or doors and instead made progress in the crowded urban texture while breaking through walls, walking through roofs, traversing the inside out. Such traversal of public and private spaces—of inside and outside—stands for a larger shift in the IDF strategic thinking. This change meant to induce elasticity, dynamism and creativity within the IDF operational logic. The street and the door are thresholds that delimit a state of fragility and exposure for the troops; walking through the walls, the soldiers rewrite the space, adopt to chaos and non-linearity, constantly shifting the camp’s inside and outside. According to Weizman, military strategists came with such tactical thinking by reading poststructuralists, postcolonial and constructivists radical thinkers such as Deleuze and Guattari, George Battai and the swiss architect Bernard Tschumi. In his article Weizman cites the testimony of one Palestinian woman who was sitting in her living room, watching television, when soldiers broke through her wall. She describes how one of the soldiers started screaming at her “get inside.” Her response to the soldier was: “but I am inside.” The city, like the tunnel in the 2021 maneuver, is no longer the site of battle, but the weapon itself.

[Fig 3: Camero’s Through Wall imaging demonstration. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqs2OFu_NM4]

Back in 2006 Weizman also foresees that the shift in strategic thinking and movement will soon be translated into vision technics, allowing the soldiers to see through walls. Like the paradigm offered by Keenan, media technology steps in to replace the physical body rather than it’s being put in risk. With less dynamism and creativity, the IDF is consistent with using traversed geometry—as in turning the inside out—in its response to Palestinian resistance. Facing Gaza’s underground web of tunnels, Israel started building a massive underground wall around the Gaza strip. The majority of the wall, planned as 65 kilometers of reinforced concrete with the cost of milliards of dollars, is invisible. Instead of a wall resurrected upwards, the wall is built into the ground, digging up the soil, filling it with concrete, messing up geological formations. Geologically, the Gaza terrain is characterized as “soft earth,” consisting of high sand content. The underground wall is built using a relatively new engineering technology called Slurry wall. In addition to its concrete formation, the wall is said to embed movement-capturing sensors. What is interesting with the Slurry wall is its traversed attention. The wall corresponds with the environment—the sandy, soft soil—rather than the human factor. The sensors, are doing the opposite. Together, both sand and human bodies are what the wall is meant to block as infiltrating threats.

Gaza’s underground is traversed not only by means of concrete and walls, but by further unearthing. One of the means with which the IDF tracks tunnels is conducting systematic digging into the ground. With this, the IDF excavates earth samples that can indicate the alternation of underground consistencies. It uses sensors to track tectonic shifts in geological depth. This literally means fighting digging with more digging. While the ground is being constantly monitored and filtered, what is most striking is its constant hollowing as means of weaponizing.

The Technological Lab for Tracking and Exposing Tunnels, an IDF unit established in 2016, has in its arsenal a combined technology that uses sound, seismic sensors and thermal imaging in order to track activity done underground. In a video released by the lab, red and rainbow-color emissions are patterned on a background of a blue screen. A title that opens the video explains: “identifying the sound of digging through seismic sensors” (highlighting in the origin). Nicole Starosielski describes heat-based media as producing a “radiant spectrum,” marked by thermal emissions. Thermal imaging most common use in warfare is to track the movement of bodies in space or to track consistency attached to or within bodies. For example, the use of thermal vision to track boats carrying refugees drifting in the Mediterranean or the use of thermal vision to detect weapons and explosive carried on bodies. With these usages thermal vision reinforces the notion of surface, demarcating bodies or land as containers with an external layer, a shell. But what we see in the video released by the Technological Lab for Tracking and Exposing Tunnels is much more abstract and corresponds first with the ground, indicating human activity via the medium of the earth. As such, thermal imaging abstracts both soil substance and bodies.

Thermal vision traverses vision: corresponding not with a scale of brightness and light but one of hot and cold, or the accumulation of energy. A former war photographer told me a story about a sniper who was assigned to sit in a house for an entire month and surveil a certain suspect in the neighboring house with a thermal Weapon Sight. For the entire month the sniper saw the house inhabitants, the suspect and his wife, mostly as two stains of energy moving in space. After a while he learnt to discern one body from another – the suspect from his wife—based on their energetic consistency. This story awkwardly brings together surveillance and intimacy, interiority and recognition. It made me think about the radical abstraction of space and bodies by means of penetrating and traversal. In the abstraction, under the surface, where bodies are no longer (or, perhaps, more than ever) delimited, and the space is turned inside out—despite the diffusion, what seems to be consistent are narratives of hostility pertaining to both landscape and subjective agents.

(Fig 4: screen shot from a video released on Israeli news depict the identification and capturing of Hamas combatants emerging from a tunnel. Released July 17, 2014)

III.

Vital Lethality

In his article Weizman notes the importance of metaphors related to animal behavior in poststructuralist military tactics, such as swarm intelligence or worms that eat their way through substance. Like with The Snake, the means of operating and the strategic thinking behind it, entail something vital that draws from organic and biological life.

In 2019 another press release announced that The Snake is now operative in high-precision invasive medical procedures. This adds to its vitality an additional component. Like other technologies presented here, the technology itself is used to penetrate both the unknow subterranean of the ground and of that of the human body, exploring depth. From its very initiation at the news item, the rhetoric around The Snake is that of a technological development meant for both elimination and rescue, defense and care. The tunnels themselves, an elaborate network of dozens of miles-long underpasses also known as “The Gaza’s Metro” are used, among other things, as a supply chain for food, construction materials and medicine for a city of over 2 million residents being put under blockade for over 14 years, held on the verge of a humanitarian crisis, on the verge of disaster. The tunnels are a source of life.

Laleh Khalili contends that counterinsurgency is a liberal warfare that entails biopolitical use of power and draws on a legal and humanitarian discourses. It means that side by side with its use of armed power it attends life and nurtures them and that the way it uses its power to take life also includes some thinking on how to preserve life. The terminology of surgical precision, of targeting only affected organs, is very much the product of such biopolitical warfare. Biopolitical warfare entails a conundrum under which killing can pass under humanitarian law. Biomatric warfare, a division that includes an explosive fish or an army of arthropodous robots, enable operations of precision and distance, that are vital as much as lethal. With surgical precision warfare is not about killing the occupied population, but about removing the sick part (this is true of course for a pre-October 2023 approach. Today, Israeli military power makes no distinction between civilian population and Hamas combatants, as the high number of civilian casualties show). This resonates with a medical approach in which sickness is isolated to specific organs and so does the treatment, rather than addressing the body as a whole. Khalili demonstrates her argument by analyzing a discourses of “democratization” or the legal and public attempts to ethicalize war, that perceives war as beneficial for the civilian population, a form of care.

IV.

Deep Sovereignty

The video demonstration of The Technological Lab features the medium of heat, but also that of sound. With this demonstration of how to listen to tunnels, let me collect some points about what I termed penetrative aesthetics. First, like in the case of thermal media, the operative use of vibrations entails a variety of applications in which the depth of the earth and that of the body coalesce. Sound vibrations, for example, are used today in experimental pharmacology to target and apply drugs only to affected organs. Drugs are capsulated in air bubbles and, with an external exposure to vibration, are mobilized inside the body. Consistent with the way it is used in warfare, medical media is a means of penetration, precision, targeting and isolating a part from the whole. Second, and perhaps somehow contradictory, sound in these cases is measured through resonance, which destabilizes a sense of source as well as the unicentricity and directionality of what we call an operation. Operating with sound means operation with a level of uncertainty and indeterminacy. Here it should be noted that with all the high tech and empirical measures, the IDF tunnel warfare is extremely speculative. Thirdly, sound is one measure in an assembled technology that captures movement (sensors), energy (thermal vision) and echo/depth (sound) all of them cater to an image. This image is positioned beyond the threshold of visibility, transgressing indexicality as the photographic image main logic, and certainly needs a trained viewer to read it.

Through the tunnels of the ear things get further abstract and speculative. To the technological assemblage of cohering and controlling depth I want to add one last operational field, also directed at spheres of interiority. Resilience, as a set of psycho-pedagogical practices had become a prevalence civil infrastructure in conflict ridden geographies. What is termed in Israel the tunnels threat is not just handled on the level of security, but concerned the wellbeing of the civilian population living across and around Gaza. Projects ranging from mindfulness workshops to neuro-feedback experimentation, as benefiting as they are for the population, are meant to rehabilitate and therefore shape civil society according to security logic of animosity.

These practices call to mind what Luciana Parisi and Steven Goodman term Mnemonic Control, a biopolitical horizon where our very cognitive system is already patterned along different forms of governance and management. Parisi and Goodman look at advertisement as forming cognition and shaping the percepts of an uber-consumerist subject in a capitalist regime in realms of desire and subjectivity. I am interested in thinking of neurofeedback and neurodesign as means of interiority that cater to resilience in a biopolitical warfare. Cultural theorist Joshua Neves notices a continuum between the mediated environment of the Smart House or the internet of things, and the Smart body or the internet of bodies. He notices how a series of technologies directed at optimizing our bodies no longer work according to the logic of extension to the body, a logic of prosthetics, but rather are mutually-constituted with the body. Here media is situated in interiority, constitutive of inner organs and mental faculties. This leads him to explore the new neurological directions taken by the pharma industry, among them microdosing.

Mindfulness, certainly a beneficial practice for the contemporary neoliberal subject, is a way to channel psychic energy in a way that makes one present, aware, goal oriented and able to act. Similarly to the reduction of the image to a sphere of operation, what is at stake here is directionality and output. Neurofeedback was conceived as a way to avoid a more invasive medical or surgical intervention in cases of neurological and psychological illness. It uses videogame or 3D simulation platforms to train our minds to re-channel neurological transmissions and recharge mnemonic patterns. In military context it is used to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (we can see this being demonstrated in Harun Farocki’s video Serious Games. Some experimentation with the technic is conducted by Israeli labs, experimenting on Israeli soldiers with funding by the US military). Neurofeedback is thus used for the aftermath of battle as a form of maintenance in a perpetual war. This too is a biopolitical thinking of sustaining and supporting life, of providing care, that coalesces with improving and optimizing the bodies and minds of combatants. Resilience, according to Jose Brunner and Galia Plotkin Amrami, emerges as a discourse of survival in the neo-liberal state. They contend that the kind of civil contract that contemporary sovereignty has with its citizens does no longer includes prevention of harm, but rather commissions resilience as a sort of individualized protection kit from an imminent disaster. With resilience, rather than understanding the state as a unified political body, there are the optimized bodies of individual citizens.

As I showed here, I come to this study through working on security and military applications as a way to ask questions of sovereign modes of governance, containment and cooption. Going inside demonstrate the expanded horizons of control—control of minds and bodies, control of territory. Like the air, sovereign territory is hard to mark in the depth, where things become obscure. It involves fiction and speculation and an entire arsenal of technologies and technics to manage and monitor geological and biological movements.

V.

Epilogue

The Snake itself is partly a fiction. While the news release celebrated the avantgarde technology as the future of warfare, so far it is not even clear if The Snake was ever in use. An additional incident unearths the logic of subterranean control all together. On 6 of September, 2021 six Palestinians escaped the Gilboa Prison in Israel, a secured site where thousands of prisoners are held as administrative detainees. Among the six was Zakaria Zubeidi, a symbol of Palestinian resistance and endurance who fought in Jenin in 2006 when Israeli soldiers were walking through walls. The story of the escape sparks the imagination. The prisoners escaped through 22 meters of narrow tunnel they dug under the prison’s showers. Investigated about the escape after being caught, they explained they walked around the prison banging on the floor in order to locate the hollowest section of the prison. The wet soil under the shower turned out to be the ideal location. They dug the tunnel using whatever they could get—mostly spoons—and spread the content of the now hollowed passageway across the prison ground, turning the inside out. Among the many memes and viral images circulated frantically in social media after the escape, one, made by film scholar Ohad Landsman, paraphrased a citation from the 1994 film The Shawshank Redemption that features quite triumphally a similar pattern of escape. The citation is as followed: “Zacharia Zubeidi, who crawled through a river of shit and came out clean on the other side.” The sewage brings back the body in its traversed form. The many images of rogue tunnels, being penetrated by a sort of photographic fiber indeed have a rectal element to them. The story of the escape—a reality bigger than any fiction—perhaps traverses or alters the channels of control, reclaiming the tunnel as a means to subvert and disturbs deep sovereignty.

(Fig 5: the Gilboa Prison Tunnel)

Dr. Laliv Melamed is a Professor of Digital Film Culture at the Goethe University, Frankfurt. She specializes in non fiction film and media. She is the author of Sovereign Intimacy: Private Media and the Traces of Colonial Violence (CUP, 2023), as well as articles, short essays and book chapters on Israel-Palestine, media, affect and politics that appeared in JCMS, Discourse, American Anthropologist Review, Social Text (online), World Records and NECSUS, among others. Her current book project studies the entanglement of military optics with cultural imaginaries of violence, civil consent and secrecy. Additionally, she has worked as film programmer and curator for DocAviv, Artport, Oberhausen Film Festival, The Left Wing Film Club, and the Israeli nonprofit Zochrot.